Patient communication skills

About how a specialist can build healthy relationships with his patients in the book by J. Silverman, S. Kurtz, J. Draper

“Forming a relationship with the patient is the key to the success of any consultation in any situation.” It is very important for a specialist in the field of aesthetic medicine to master the art of psychology in order to find an individual approach to the patient.

“Communication Skills with Patients” - a book by the authors Silverman J., Kurtz S., Draper J. (translation from English edited by Sonkina A.A. ). The full version of the book is available for purchase on our website via the link.

Representatives of social professions, in addition to practical skills in their field of activity, need to develop psychological skills. In the activities of aesthetic medicine specialists, this is due to the fact that the factor of communication with the patient directly affects the result of the procedure or manipulation performed, as well as the possibility of developing a further personal brand. Also, a healthy rational relationship with your ward is the protection of the specialist’s mental health, the prevention of emotional burnout and anxiety and other disorders against the backdrop of stressful work.

For your attention, Chapter 5 of the book “Communication Skills with Patients” Silverman J., Kurtz S., Draper J.:

"Building Relationships"

Introduction

There is one clear message that runs through this book and its accompanying book: relationships matter. They have a major impact on communication in medicine, on the people involved, on medical care itself and its results.

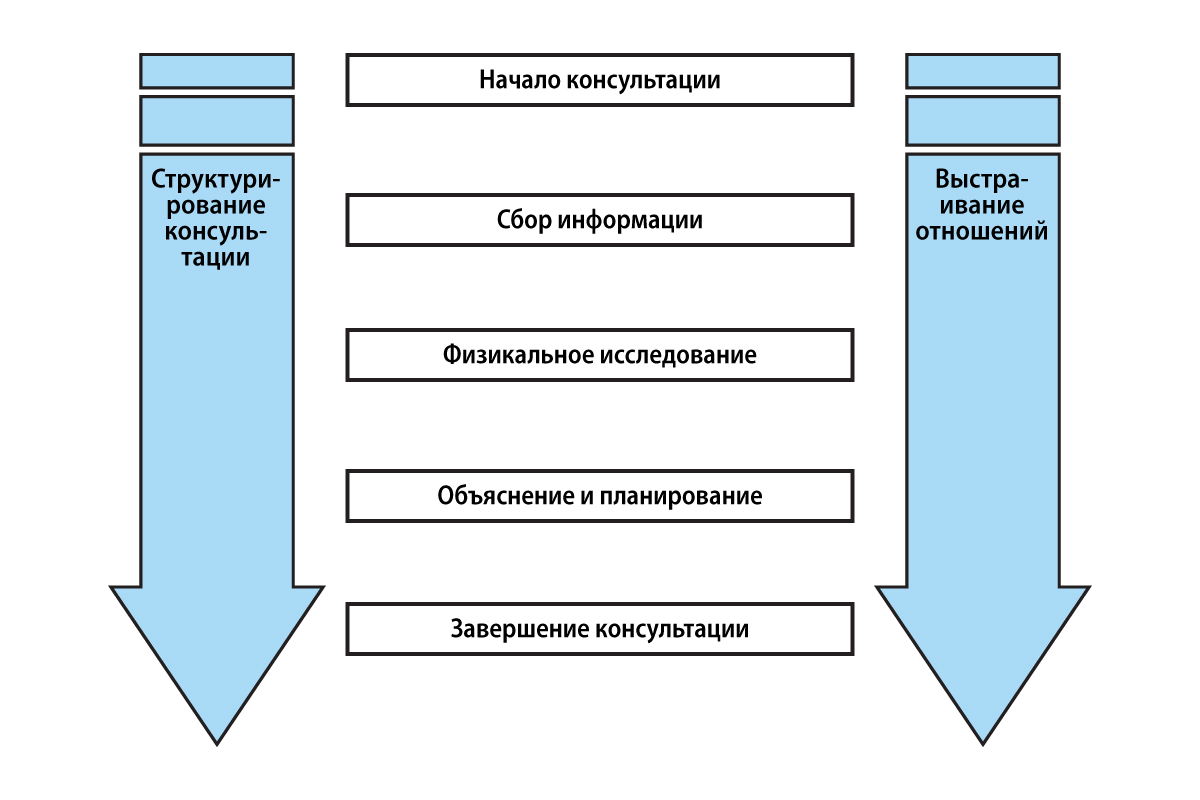

As shown in Fig. 5.1, during a consultation, five tasks are performed sequentially. In contrast, both relationship building and consultation structuring run throughout the consultation. Relationship building occurs in parallel with five sequential tasks. This is the cement that binds the consultation into a single whole.

Figure 5.1. Structuring the consultation

Almost all of the skills we suggest in this book for solving sequential problems also contribute to establishing a strong relationship with the patient. However, we intentionally place this overarching task in its own category and dedicate this chapter to it to highlight its importance and to highlight important relationship-building skills that apply throughout the consultation and do not fit into any one task.

It’s easy to take relationship building for granted or forget about it altogether. As the doctor conducts the consultation, trying to understand both the patient's illness and his experience of the disease, it is often the sequential components of the consultation that dominate the consultation. Yet, without a strong focus on relationship skills, these more “concrete” tasks will be much more difficult to accomplish. Building relationships during a consultation can even be an end in itself—sometimes the doctor’s role is reduced to providing psychological support. But in most cases, relationship building makes a significant contribution to achieving all of the goals of medical consultation that we described in Chapter 1, namely accuracy, efficiency and support, increasing satisfaction of both patient and physician, and promoting partnership and collaboration. Building relationships allows the patient to tell their story and explain their concerns and concerns, promotes compliance, and prevents misunderstandings and conflict.

Forming a relationship with the patient is the key to the success of any consultation in any situation.

Often, especially when consulting with specialists, the relationship between doctor and patient is short-term. In these cases, mutual understanding is extremely important - it allows the patient to feel comfortable discussing his problems with a stranger and to get the maximum benefit from the consultation. The doctor, however, faces additional difficulties: he must be able to build a relationship in a short time and often against the background of significant anxiety of the patient (Barnett, 2001).

Building relationships also opens up the opportunity to consider the practice of medicine in a longer term than we have done so far. In many cases, the physician-patient relationship extends beyond one consultation and communication continues across multiple appointments (Leopold et al., 1996). There is a need to maintain secure, trusting relationships over time, even when there is no hope of healing (Cocksedge et al., 2011). Many doctors believe that long-term relationships with patients bring them the greatest satisfaction in their work.

Patients want their doctors to be competent and knowledgeable, but they also want a connection with their doctor, to be understood and supported in their struggles. Concern about strengthening relationships results in patients being more satisfied with their physicians and physicians experiencing less frustration and greater job satisfaction (Levinson et al., 1993).

Bensing et al. (2011) confirmed the views of patients: non-medical people in 32 focus groups across Europe were asked to formulate “advices” to doctors after watching videos of consultations and assessing the quality of communication. The most common advice related to the importance of nonverbal communication, attention to the patient, listening skills and empathy.

Relationship skills are becoming increasingly important not only in medical consultations, but also in relationships between health care professionals. A book about a series of studies showing how powerful relationships help performance in the airline industry (Gittel, 2003) includes excerpts from a larger study (Gittel et al., 2000) in which the authors compared performance and performance in joint replacement surgery in nine hospitals located in New York, Boston and Dallas. Some of these hospitals have invested heavily in recruiting staff and subsequently training them in “relational competence,” that is, the ability to interact with others to achieve common goals. Other hospitals instead simply sought highly qualified specialists—a tendency among these hospitals to neglect relational competence that was most evident in the hiring of physicians. This study showed significant differences between hospitals in coordinating relationships among employees with a common goal that significantly improves patient care. As an illustration, Gittel (2003) reports that a 100% increase in such relationship coordination resulted in a 31% reduction in length of stay, a 22% increase in quality of care, a 7% increase in postoperative pain freedom, and a 10% increase in postoperative mobility. 5%. As concluded by Gittel et al. (2000), jobs that require a high level of professionalism also require a high level of relational competence to coordinate one's work with others. One study participant put it this way: “We have moved from human-delivered patient care to system-provided care. Now individual skill is not the only thing that matters. Coordinated efforts are important."

Thus, in medicine, relationship skills and relational competence are important both in patient-physician consultations and in relationships between health care professionals.

Whether we are talking about patients or employees, we agree with Jody Hoffer Gittel that relational competence is essential to understanding the contributions of each professional. This chapter focuses on building the doctor-patient relationship during a consultation, but the skills presented apply to building relationships in a broader context, such as with colleagues, coworkers, or patients' loved ones.

The above argues in favor of relationship-oriented medicine. It is based on a biopsychosocial model, akin to patient-centered medicine, and adopts a personalized, partnership-oriented approach (Suchman et al., 2002). It is a relationship-centered approach to care and treatment. This view of consultation and health care in general helps focus attention on the critical need for relationships among patients, physicians, families, other caregivers, health care settings, and communities (Tresollini and the Pew-Fetzer Force, 1994; Beach and lnui , 2006). This approach recognizes that doctor-patient communication and relationships take place within an organization and are therefore influenced not only by the needs and skills of individuals, but also by the values expressed in the rules and procedures of the organization, and how people within the organization relate to each other. to a friend and how they are treated (Suchman, 2001). This is consistent with the work of Aita et al. (2005), which examined primary care settings in the United States. They showed that individual physicians operate within personal and professional value systems, as well as within the value systems of their practices. In their sample of physician practices, a key factor in providing patient-centered care was the ability of physicians to create an environment in their practice and administration that emphasized patient-centered values. Suchman et al. (2011), in a book documenting major changes in health care, provide excellent insight into relationship-centered care and management, along with several examples detailing how to apply these approaches to implement change and improve various aspects of health care.

The skills and concepts discussed in this chapter, along with those related to building relationships in sequential counseling tasks, provide the clinician with the means to improve his or her relational competence and ability to provide relationship-centered care. As Jody Homer Gittel said, “The first step is to become a caring person, the second is to find ways to be caring every day, as well as in times of deep crisis.”

David Sluyter, a former fellow at the Fetzer Institute and editor of a book on emotional intelligence, introduces into this discussion the concept of personal abilities, which can be innate or learned. According to him, “it is really important to have both abilities, which can probably be acquired through self-improvement and personal growth, and the skills to communicate these abilities to others, which is rather a matter of training skills and which, perhaps, should be taught separately.” He gives this example: “A person can be very loving and forgiving (abilities), but not very successful at loving and forgiving. That is, he may not have enough skills to put [the abilities] into practice.” We like to think of compassion and participation as abilities rather than attributes or qualities—“abilities” somehow imply more opportunities for growth and development (D. Sluyter, personal communication, 2004).

The full version of the book “Communication Skills with Patients” by Silverman J., Kurtz S., Draper J. (translated from English, edited by A.A. Sonkina) can be purchased at the link

How does nonverbal communication differ from verbal communication?

What are the differences between verbal and nonverbal communication (Verderber and Verderber, 1980)?

Verbal communication is discrete, with clear boundaries: we know when the message has ended. Nonverbal communication, on the other hand, is continuous—it continues as long as the meeting continues. We cannot stop our nonverbal communication (Watzlawick et al., 1967) - even if everyone is silent, the atmosphere is filled with messages. The difference between comfortable and uncomfortable silence is determined by our nonverbal communication.

Verbal communication is carried out at each moment in a single way - either oral or written, while non-verbal communication can be carried out in several ways at the same time. We can send and receive all of the nonverbal signals listed in Box 5.2 at the same time, and all of our senses can perceive them simultaneously.

Verbal communication is usually controlled, while non-verbal communication occurs on the edge or beyond our awareness. Nonverbal communication is used consciously: for example, we intentionally give nonverbal signals with our voice or body, head, and eye movements to coordinate turn-taking in conversation. However, nonverbal communication also occurs on a less conscious level. In this case, there may be “leaks” of spontaneous signals that we are not even aware of and which represent our true feelings better than conscious verbal remarks. DiMatteo et al. (1980) have shown that this is especially true for posture and movement.

Words are more effective in conveying certain information and in communicating our ideas and thoughts. Nonverbal communication, on the other hand, serves largely as a channel for conveying our attitudes and emotions, revealing how we present ourselves to others and how we relate to them. Nonverbals convey much more information about sympathy, responsiveness, or dominance than verbal ones. Nonverbal communication plays an increasingly important role when a person is unable or unwilling to express feelings openly in words—for example, when cultural taboos prohibit disagreeing with an elder or when words fail to express love, grief, or pain (Ekman et al., 1972 Mehrabian 1972; Argyle 1975).

What are the lessons for doctors?

Physicians should monitor their own and their patients' nonverbal behavior.

Reading patients' nonverbal cues

The ability to “decipher” nonverbal cues is essential if we are to understand patients' feelings. The cultural norms of the medical world make it difficult for patients to verbalize their feelings, and they hesitate to express their thoughts and feelings openly, but instead use indirect or covert methods (see Chapter 6, pp. 177-88). Nonverbal cues may therefore be one of the few clues to the clinician that the patient is willing to communicate concerns about a problem.

However, just because the patient is sending spontaneous signals of true feelings does not mean that you are able to interpret them correctly simply by noticing them—there are many sources of distortion and misunderstanding when receiving nonverbal messages. In order for the interpretation of nonverbal behavior to be correct, it is important not only to carefully observe it, but also to check your perception verbally. Your interpretations and assumptions may or may not be correct, so they need to be checked with the patient. Testing assumptions encourages the patient to further explain his thoughts and feelings; it is doubly useful: both the doctor and the patient avoid false interpretations and discover more information.

The skills of picking up nonverbal cues and checking them verbally ( “You look upset. Do you want to talk about it?” ) are described in Chapter Z. of the book “Communication Skills with Patients” Silverman J., Kurtz S., Draper J. (translated from English, edited by Sonkina A.A.)

Capturing nonverbal signals not only helps the doctor understand the emotional side of the patient’s illness, but also has great diagnostic value in itself. Reading the nonverbal cues of depression is an essential part of diagnosing the disease itself (Hall et al., 1995), and emotional disorders that are only hinted at by nonverbal cues are often the cause of physical illness.

Nonverbal signals from the doctor

Likewise, without attention to your own nonverbal communication skills and the signals you convey through nonverbal channels (“encoding”), many of your other communication efforts may fail. If your verbal cues conflict with your nonverbal cues, you risk, at a minimum, causing confusion or misunderstanding, and at maximum, your nonverbal cue will prevail. Nonverbal skills, through eye contact, posture, body position and movement, facial expressions, timely responses and voice, will help you demonstrate your care to the patient and form a beneficial relationship; in contrast, inattentive behavior will shut down interactions and interfere with relationship building (Gazda et al., 1995). The inequality between the doctor and the patient in the capabilities and control of situations forces the patient to be especially attentive to nonverbal signals about the doctor's attitudes and position. Patients rarely ask for confirmation of verbal cues they perceive and usually base their impressions on nonverbal messages.

Correct and effective communication skills need to be constantly developed and improved. Scientifically proven psychological techniques, methods and original advice to a specialist for building a healthy relationship with a patient can be found in the book “Communication skills with patients” Silverman J., Kurtz S., Draper J. (translated from English, edited by Sonkina A.A.) , which is available for purchase via the link.

Read also

- How to work with anxious patients in aesthetic medicine

- Psychology and communication skills: how to establish communication with patients

- Lessons from the pandemic: strengthening the immune system and taking care of health as a priority

- A patient with body dysmorphic syndrome: how to help and not harm?

- Psychological support for patients with acne: expert opinion

- Beauty is timeless: current trends in aesthetic medicine